The day I arrived in Caens was a beautiful, hot, sunny day: blue skies, with hardly a cloud to be seen. It was an ice-cream-and-bare-feet day. The next day – the day I went to find the grave of my great uncle – I woke to a completely overcast sky and cool temperatures. Rain, or at least drizzle, was forecast. It seemed appropriate.

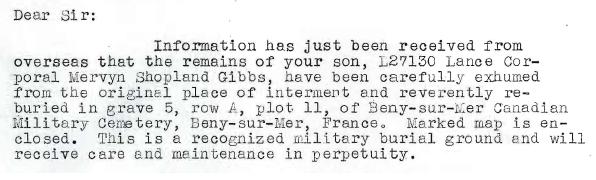

No one from my family has ever visited the grave, so when he knew I would be in the area my Dad asked me to go and take some pictures. He doesn’t ask for much, my Dad, so I was happy to do this. He also gave me copies of the letters from the Department of National Defense about the whereabouts of the grave. They were terribly sad. I can’t imagine what it must be like to receive a letter like that.

So when I arrived in Caen yesterday my first stop, after a sweaty 20 minute trudge from the station, was the Tourist Information Office (or “TI”, as we “RTW” types like to call it). I had a bit of a tricky task – the Canadian War Cemetery at Bény-sur-Mer is not exactly on the beaten track, so I needed some advice on how to get there and back. The woman who helped me was really good and very friendly and tolerated my poor language skills and odd requests with a smile. However it seems that the good people at the Caen TI are not often called upon to get visiting Canadians to and from a cemetery 20 km away. Wikipedia, on the other hand, made it sound like finding the place would be a simple matter:

The cemetery is about 1 kilometre east of the village of Reviers, in the Calvados department, on the Creully-Tailleville-Ouistreham road (D.35). It is located 15 kilometres northwest of Caen, 18 kilometres east of Bayeux, and 3.5 kilometres south of Courseulles-sur-Mer. The village of Bény-sur-Mer is some 2 kilometres southeast of the cemetery. The bus service between Caen and Arromanches (via Reviers and Ver-sur-Mer) passes the cemetery.* The cemetery can be accessed any time, and tours of the cemetery are available through companies offering tours of historic D-Day locations in the area. The cemetery is easy to find, and plenty of parking is available.

I’m sure that’s all fine if one has a car and a proper map. However, if one is à pied, it’s another matter. And to confuse things further, it turns out that the Bény-sur-Mer cemetery is actually closer to the tiny town of Reviers than it is to the slightly larger eponymous town of Bény-sur-Mer.

Nevertheless, there is a way. There really is a bus that goes from Caens to Reviers (Ligne 6, from Place Courtonne, €3.20 one-way, for future reference), and it’s a short walk from the town to the cemetery. The first bus of the day leaves Caen at 12:37 pm and arrives at Riviers at 1:12 pm. Perfect. The problem comes if one desires to return from Reviers to Caens. The last (in fact, only) bus from Reviers to Caens departs at 1:36 pm, allowing just 24 minutes of time in Reviers. I ask you, what kind of slack-jawed cretin devises a bus schedule like that? Honestly.

Back at the TI we looked at alternatives and determined that the simplest thing would be to reserve a taxi to pick me up at the cemetery and deliver me back to Caen. Not the cheapest option, but the one with the greatest chance of success. By this time I’d reached the very limit of my ability in French so the long-suffering woman at the TI phoned and made the reservation for me. And then I decided I should probably leave because they were actually turning out the lights.** No matter, I was sorted.

The next morning I got the bus as advertised and had no trouble finding the cemetery. I really was a short walk from the town, and it’s surrounded by farmland, which seemed very appropriate. I knew I'd found it as soon as I topped the hill, and just seeing this had me blinking back a few tears:

My first stop was the cemetery register. Every war cemetery I've been to has a register - it's just a plain bunch of bundled sheets that lists every marker in the cemetery, ordered by last name, along with a few details about the soldier. Some entries have notes about medals won - I saw one at Essex Farm about a Victoria Cross winner. And there's always a Visitor's Book too, where you can sign your name and leave a message. They're normally stored together in a little recess in a wall, away from the elements.

I had no trouble finding the entry I was looking for:

There was nothing for it then but to go find the grave, which was a simple matter. He was right where he was supposed to be – Plot 11, Row A, Grave 5.

It was really emotional standing there in front of that headstone. Ypres was emotional too, but in an overwhelming and abstract kind of way. This was personal. Here was someone I’d never met, in fact never had a chance to meet, but who was still part of me. Mervyn Gibbs was the oldest son of four siblings – he had one brother and two sisters. One sister was my grandmother and one is my great aunt who I still visit when I’m home. If it hadn’t been for that war I might still be able to visit him too. Granted he’d be about 88 years old by now, but that would mean he’d have had 65 years more life than he got.

I’ve been thinking about this side-trip for a while, and a few days ago I realized that I wanted to leave something at the grave just to show I’d been there. Just to show that someone had been there to personally acknowledge the sacrifice of this particular man. I thought about flowers, but that didn’t feel right. It felt like it should be something from home, but I really couldn’t think what that might be. I could see that people sometimes leave Canadian coins, but I’d long since got rid of any of those. And some people simply balance small pebbles on the top of the headstone, but that didn’t seem right either. Then I figured it out. I cut the little Canadian flag badge off of my daypack, and I left it tucked into the plants at the base of the headstone.

It feels strange to be without it – like I’ve lost a bit of my identity. But it feels better knowing it’s there, and it seemed right that it should be something that had traveled as far as he had. At 23 years old he came all the way over here to fight for people and a place he’d never known, and he died doing it, and now he’s here forever. That really struck me – how very very young he was and how very very far from home. Now at least there’s a little bit of home with him.

The whole cemetery is fairly large – slightly bigger than Essex Farm at Ypres, but much smaller than Tyne Cot. It contains 2049 markers, many of which are for those who were killed in early July 1944 in the Battle for Caen. And I’m happy to report that it is immaculately kept – the grass is neatly mowed, and the leaves falling off the maple trees must be raked up regularly. In fact there was a gardener there this afternoon tidying things up, and he was kind enough to take my picture for me.There’s also been an extensive program to replace many of the markers due to faster-than-expected deterioration. I could see some of the ones that hadn’t been replaced yet, and they were indeed looking a bit sad. The marker for my uncle is almost certainly new – it was pristine. The people at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission do good work.

And then I looked around, and I took a lot more pictures, and just sort of thought about things. I was there for about an hour and a half before my cab arrived, and it was a good amount of time. Long enough that it felt appropriate and respectful, but not so long that I was spending more time thinking about how it really must be time to have something to eat*** than about what I was there for. And then the cab came and whisked me back to reality, or at least what passes for reality for me these days. All that remained was to try and find a late lunch and to gather my thoughts about the day. And so I did.

What to say in closing? All I can think of is this: Thank you, Lance Corporal Mervyn Gibbs. You gave your name to my father and you gave your life to us all. I wish I could have known you.

Rest in peace.

Lance Corporal Mervyn Shopland Gibbs, died July 8, 1944, Age 23.

Lance Corporal Mervyn Shopland Gibbs, died July 8, 1944, Age 23.

* In fact this is true, but only between July 3 and September 1. Convenient.

** They really were, but I hasten to add that everyone at the Caens Tourist Information Office was unfailingly pleasant, with nary a Parisian “Pffftt” to be heard. The fact that they turned out the lights on me is just because it was 6:02 pm and they closed at 6:00 pm.

*** And let me tell you whatever crazy Frenchman decided that every decent restaurant in Caens must be closed between the hours of 3pm and 6pm should be forced to eat at McDonald’s for eternity. And super-size that, please. I ended up noshing on a sandwich and beer in my hotel room, which is in flagrant disregard of the notice declaring Il est interdit de manger dans les chambres. Hrrummmph.... Il est aussi interdit de faire la lessive (already done it), d'accrocher du ligne aux fenêtres (easily accomplished) et de cuisiner (slightly more complicated but not impossible). If I put my mind to it, I could manage to break all the rules before sunset.

5 Comments:

A very moving post today, Pam. Made me cry.

I'm in tears as I type this. I can only imagine how you must feel being there. Take care...(((HUGS)))

Beautiful

Tears here too. I am so glad you left your flag. Lovely gesture on your part.

Just getting caught up on your travels Pam - the picture of your little Cdn flag on your Uncle's marker made me teary - it was perfect.

Post a Comment