This is not a happy blog post – if you’re having a rough day, I’d recommend skipping it. There just isn’t a way to treat this subject lightly because frankly, it beggars belief. The atrocities committed by the Khmer Rouge on the people of Cambodia between 1975 and 1979 are so horrific that it’s difficult to process. For those of you who are, as I was, mostly ignorant of the history of Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge, here’s a primer of what I’ve absorbed from Wikipedia and the documentation at the sights I visited in and around Phnom Penh.

The Khmer Rouge were a communist organization that took power in Cambodia, seizing control of the capital Phnom Penh, on April 17, 1975. Led by the notorious Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge’s particular brand of communism came to be guided by four principles:

- Total independence and self reliance

- Preservation of the dictatorship of the proletariat

- Total and immediate economic revolution

- Complete transformation of Khmer social values

In practice this meant that when the Khmer Rouge troops took Phnom Pen, they immediately started transporting its residents out of the city to become farm labourers - “rusticating” the urban population who would be transformed through hard labour into part of their new rural, classless society. Phnom Penh, a city of 2.5 million, became a ghost town in just three days; other urban centres were emptied as well. The Khmer Rouge abolished currency, banks, normal schooling, proper hospitals, free markets, foreign clothing, religious practice and traditional Khmer culture. There was no public or private transportation and no private property. Most of the population was bent towards attempting to triple rice production from previous levels – to help lead to independence from outside aid. Many died from starvation and disease, at least partly because what medical aid was available was often primitive because no outside medical expertise was allowed.

Food was available on communal farms where people were virtually imprisoned, but rations were small and hunger was constant. Even foraging for berries to eat was considered “private enterprise” and could result in death. Those who survived the back-breaking work and famine were subject to brutal and arbitrary torture and execution – anyone suspected of being a professional or intellectual was killed; in some cases simply wearing eyeglasses was considered an indication of literacy, and could mark someone for death. Others subject to torture and death included anyone with a connection to a foreign government or to the former Cambodian government, and those belonging to ethnic Chinese, Thai or other “non-Cambodian” ethnic groups, Christians, Muslims and Buddhist monks. The brutality of the regime is chillingly summed up in one of their mottoes:

"To keep you is no benefit. To destroy you is no loss."

Those marked for death were transported to the killing fields – and here I got a rude shock. Having heard the term “killing fields” before, I’d always assumed it was one area. In fact, there were 343 different killing sites around the country and 19,440 mass graves have been discovered, containing more than one million bodies. Add to that the number who died of starvation, overwork, or inadequate medical care and the total death toll rises to something in the neighbourhood of 2.2 million. People were trucked out to these killing fields and murdered as soon as they arrived, often bludgeoned to death with farm implements or simple chunks of bamboo in order to save on ammunition. Near the end of the regime the killings grew more and more frequent and so many condemned were brought to the fields that the Khmer Rouge had to create holding pens in some places because they simply couldn’t kill everyone who arrived each day. It’s a scale of atrocity that’s hard to fathom.

The most visited killing field is at Choeung Ek about 15 km southwest of Phnom Penh. It’s a heartbreakingly small area dominated by a large memorial stupa containing the clothing, skulls and other bones of some of the 8,995 people who died there. I paid the $2 entry fee and, unsure where to start, wandered over to the small museum on the site. There I watched a short video, read through the museum displays, and finally walked out into the site. It’s incongruously park-like. There are trees and grass and unpaved dirt paths that wind between depressions in the ground; those depressions are the excavated mass graves.

The scene at Cheoung Ek

The scene at Cheoung Ek

Nothing is innocent at the killing fields. Among the trees are two that stand out – one large tree had a placard beside it saying it was used to hang a speaker that broadcast loud noises to drown out the cries of the victims, so that those living nearby wouldn’t grow suspicious. The other tree of note was far more sinister – it’s the one where Khmer Rouge killed babies by swinging them by their legs and smashing their heads against the trunk, where nails had been imbedded. I’m sorry if this is graphic, but it’s simply reality.

Even the pathways are eerie. They’re bare dirt, and as you walk you among the graves you can see scraps of cloth poking up through the earth. These are pieces of clothing from victims that emerge from the ground after it rains. In one or two cases I could even see what looked like bone. It was hard to believe.

Scraps of clothing on the paths

Scraps of clothing on the paths

Finally, I walked over to the stupa. Buddhists believe that human remains should be venerated and housed in special places so the stupa at Cheoung Ek contains the skulls of more than 5,000 victims of the Khmer Rouge excavated from the mass graves on the site. It’s got clear acrylic sides so you can see the contents of the different levels. The very bottom displays a mound of the clothing retrieved from the graves, and then it’s skulls as far up as you can see.

Level after level of human skulls

Level after level of human skulls

The whole place was sobering, and of course it was terribly hot out, so it was physically, emotionally and intellectually uncomfortable, and my day was only half over. Next on the agenda was the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum back in Phnom Penh. Tuol Sleng was a high school until the advent of Khmer Rouge rule when it was converted into a prison and interrogation centre. The classrooms became cells for as many as 1,500 prisoners, the windows were barred, and the balconies were covered in barbed wire. Between 1975 and 1979 an estimated 17,000 people were imprisoned there, often tortured into confessing imagined sins against the regime, or coerced into naming friends or family members who might be considered enemies.

Like Cheong Ek, it was heartbreaking – it still really looks like a school. I found the orange and white checked floor tiles particularly out of place – oddly cheery next to the bare metal bedsteads and the stark, grainy photographs of the dead displayed on the walls.

One of the classrooms that was used as a prison cell. Some others had been subdivided with hastily constructed brick or wooden barriers into tiny cells for one person.

One of the classrooms that was used as a prison cell. Some others had been subdivided with hastily constructed brick or wooden barriers into tiny cells for one person.

There was a large sign outside one of the buildings that listed the rules prisoners at Tuol Sleng were expected to follow. They were translated from Khmer into questionable English, and if the subject matter hadn’t been so dark, they would have been funny.

- You must answer accordingly to my questions – Don’t turn them away.

- Don’t try to hide the facts by making pretexts this and that. You are strictly prohibited to contest me.

- Don’t be a fool for you are a chap who dare to thwart the revolution.

- You must immediately answer my questions without wasting time to reflect.

- Don’t tell me either about your immoralities or the essence of the revolution.

- While getting lashes or electrification you must not cry at all.

- Do nothing, sit still and wait for my orders. If there is no order, keep quiet. When I ask you to do something, you must do it right away without protesting.

- Don’t make pretext about Kampuchea Krom in order to hide your secret or traitor.

- If you don’t follow all the above rules, you shall get many lashes of electric wire.

- If you disobey ant point of my regulations you shall get either ten lashes or five shocks of electric discharge.

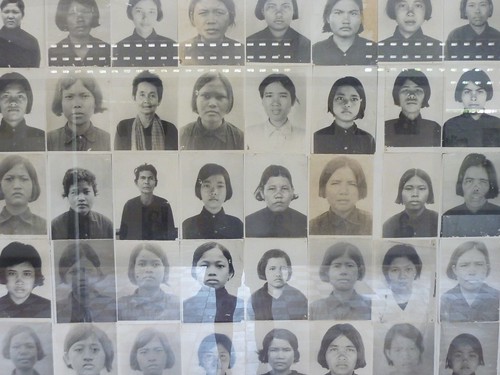

In addition to their rules, the Khmer Rouge required each prisoner arriving at Tuol Sleng to be photographed and to give detailed autobiographies. Several rooms of the museum were filled with these photographs – hundreds and hundreds of them.

Just a few of the victims of Tuol Sleng

Just a few of the victims of Tuol Sleng

I went through most of the buildings of the museum. Some rooms were empty, some had just a few artifacts, some had background information, and some displayed photographs like the ones above. At the top of one stairwell I saw a sign pointing to a movie theatre and remembered that I’d been advised there was a film on continuous loop that was difficult to watch, but worth seeing. By this time I was approaching overload, but I climbed the stairs anyways, only to discover that all the doors on that floor were locked. If there was a movie to see, I would not be seeing it, and that was a huge relief. Not long after, I left; I was done.

Though I finished with the killing fields and Tuol Sleng by lunchtime, it’s not the kind of thing you can just shake off. I went back to the hotel and did one or two small errands before showering and collapsing in my room with the lights out and the curtains drawn. I thought I might go out in the evening, but instead I spent hours uploading photos, thinking, researching, and trying to put together these thoughts on the day. Sometimes I let things percolate for a few days before I write about them, but in this case it was almost like I wanted to simply get it over with.

I started out so ridiculously ignorant of the whole episode of this country’s history that I was embarrassed when I learned how pivotal and scarring an event it was. And perhaps the most shocking thing of all was how recent this history is. When I visited the battlefields of France I was separated from those horrors by two generations, but the Khmer Rouge regime occurred within my lifetime. If I’d had the misfortune to be born in Cambodia, I’d have been six years old when Phnom Penh was taken. I’d have lived, or more likely, died, under their brutal rule. Anyone in Cambodia over the age of about 30 must have personal memories of the relocation, famine, torture and death that marked the three years of Khmer Rouge rule here. It’s all just staggering. I’m glad I’m here, and I’m glad I saw those sights and learned about the history behind them, but mostly I’m grateful to be going to bed in a peaceful and relatively safe Cambodia that seems, for the most part, to have recovered from its dark past. It’s not perfect, but it’s much much better than it was.

8 Comments:

It never ceases to amaze me the brutality that people can do to each other. And it never seems to end.

I'm really, really, really glad I live in Canada.

Pam, I have been reading your blog for awhile now and find it fascinating and entertaining. Your account of your trip to the Killing Fields was so honest and heart-wrenching and respectful. Thank you for the education and renewed love of my country (USA.)

Megan in Iowa

Sobering post...How very very sad,...

thanks for sharing this Pam.

hugs.

Thank you for sharing your experiences with us. I had many of your same emotions while visiting Hiroshima, and while the two events are far from the same, it's hard not to get completely overwhelmed after a while.

I read that you are going to Japan soon! I was there by myself last year and loved it. Very polite, quiet, beautiful country. I don't know where you plan on going, but try to get out of the bigger cities after a bit. Miyajima can be touristy but is completely worth it.

Be safe! I can't believe your journey is nearly complete!

I am so glad to be Canadian. I am so glad you posted such a forthright account... educational, makes one pause and reflect on the blessings and privileges we have in our country.

Reminds me of when I visited Auschwitz. There is this pit in your stomach that you can't shake and the incomprehensible loss is overwhelming.

Thanks for this post.

Hard to know the right way to respond to a post like this, Pam.

Glad to hear that you're able to move forward. I'm fortunate to be able to read along, as you try to make sense of this slice of the world, as you move through it. I hope that some day, in the not too distant future, that I can buy you a pint, and hear a tale or two in the first person. Be well, be safe, and take some time to goof of at the first available opportunity. It's springtime in Canada, things are looking up, and the sun shines a little warmer every day.

Jeff Scollon.

Post a Comment