I know I have been unreservedly lavish with my praise for Japan so far, so I feel like I need to admit the few things that I find annoying about being here. So here you go, the things I don’t like about Japan:

- Hotels have slightly less-than-generous check in and check out times. Check out is usually 10:00 am, which is a bit early for comfort. Check in is rarely before 3:00pm, which can also be annoying. And there’s really no room to move on those times. 3:00 is 3:00, do not ask about getting in earlier. I arrived in Granada, Spain after an overnight train ride at about 7:30 am and was genially shown to my room at 7:31; I can’t imagine the apoplexy that would cause here.

- A couple of times now I’ve come up against maps that are oriented with some direction other than north at the top. This is maddening, especially when you’re confronted with two different maps of the same place, one with north pointing to the right, and one with it pointing to the left.

- Despite the fact that the country is spotlessly clean it’s often ridiculously hard to find a garbage can. I have no idea what Japanese people do with their garbage, though if there’s like me they end up carrying it around for hours as if it’s some kind of precious keepsake.

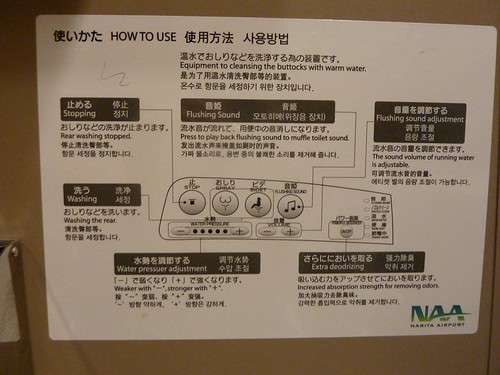

- Toilets are bizarrely and unnecessarily complicated. They usually have long instruction stickers posted nearby telling you how to operate the various automatically telescoping nozzles that spray parts of your anatomy which, if you are from North America, are probably not accustomed to being sprayed at all regardless of the many combinations of water temperature, angle and pressure you might be presented with. And sometimes toilets do things all by themselves. I first ran into this in a hotel in Kyoto when I sat down and the water started running immediately. I swear my first thought was, “Has my ass become so wide that I’m sitting on one of the little buttons on the side control panel?” Then I realized that there was a pressure-sensitive switch. I have no idea what this was for. My best guess is it’s just there to make noise to mask the sound of whatever you’re doing, which seems incredibly wasteful. In Turkey I was asked not to wash out my laundry in the sink because it used too much water, but in Japan they’re literally flushing it down the toilet. (Then again they also have clever all-in-one toilet/sinks where the toilet tank cover is a shallow basin and the water that fills the tank when you flush first comes out of a faucet above the basin so you can wash your hands with it before it flows into the tank. Clever.)

The instructions for my first Japanese toilet, at Narita Airport. I rest my case. (Also: “Equipment to cleansing the buttocks” Hee hee!)

The instructions for my first Japanese toilet, at Narita Airport. I rest my case. (Also: “Equipment to cleansing the buttocks” Hee hee!)

But on to Takayama, which I liked very much, partly because it had almost no temples and the ones it did have were easily avoided. It’s a small city (population about 95,000) and most of the interesting bits are easily reached on foot. It’s got an excellently preserved section of Edo Period homes (1600-1868), a few of which you can tour through, but most of which have been turned into restaurants and shops selling tourist tat, sakē, ice cream, glutinous rice balls (err… yum) and zillions of these creepy faceless dolls called saru-bobo (monkey babies) in sizes ranging from key-chain to impossible-to-pack.

I think it’s a town bylaw that every shop in the city sell some form of saru-bobo. I’m surprised they let me leave without one. (I did buy a souvenir though, a lovely wooden lacquered tray that’s very plain, very Japanese and not creepy at all.)

I think it’s a town bylaw that every shop in the city sell some form of saru-bobo. I’m surprised they let me leave without one. (I did buy a souvenir though, a lovely wooden lacquered tray that’s very plain, very Japanese and not creepy at all.)

The big sight to see just outside of Takayama is the Hida-no-Sato village. It’s a collection of dozens of traditional homes that were dismantled at their original sites around the area and rebuilt in an open air museum. I arrived early enough one morning to avoid most of the crowds and had a very nice, quiet time wandering in and out of the buildings . I also borrowed the free English audioguide (On cassette! Remember those?); it talked about the styles of architecture, the various industries villagers would have engaged in (like silk production), and the lifestyle of the people who lived in the houses.

One of the steeply pitched, thatched roof houses of Hida-no-Sato. They’re steeply pitched to shed the snow, which falls up to 8 feet deep in this mountainous region. It’s nice to be back in a part of the world where people have snow scoops leaning next to the back door.

One of the steeply pitched, thatched roof houses of Hida-no-Sato. They’re steeply pitched to shed the snow, which falls up to 8 feet deep in this mountainous region. It’s nice to be back in a part of the world where people have snow scoops leaning next to the back door.

One section of Hida-no-Sato contains the homes and workshops of artisans who live and work at the park, demonstrating their craft and selling their artwork to tourists. There were supposedly workshops for pottery, weaving, lacquerware and carving, but they were almost all closed the day I was there. There was one old gentleman in one of the historical houses demonstrating how to make straw sandals. Like everyone in Japan (except tour guides) he wasn’t exactly gregarious, but he let me take some pictures after I asked (in Japanese, even!). The sandals themselves look remarkably uncomfortable, but it was interesting watching the man work.

Straw sandals, under construction

Straw sandals, under construction

And just because I’ve got bandwidth up the wazoo here in Japan (which can be uncomfortable, but the toilets have a setting for it), here’s a video I took of a clever bit of water-powered machinery at Hido-na-Sato.

The automatic banging device

I did enjoy some local cuisine in Takayama, which is most famous, culinarily speaking, for two things: hoba-miso, a particular type of local miso served on a mulberry leaf over a ceramic burner (miso is the ubiquitous soybean-derived salty paste that’s used to make miso soup), and Hida beef, cousin to the renowned Kobē beef, and famous for its quality and marbling. Of course I tried both. I went to a very local place recommended by my hotel and had the miso (described by a friend’s traveling companion as “cat barf on a leaf”) which turned out to be really tasty in a salty, savoury, umami kind of way. It was also quite nice when spread onto thin slices of Hida beef grilled on the same ceramic burner. And it all goes down a treat with a glass of cold beer to put out the fire that’s lighted when you apply a slice of molten-miso-covered beef directly to your tongue.

Hida beef. Marble-licious.

Hida beef. Marble-licious.

Because Takayama is so compact I ended up being able to delve into a few more corners than I expected, which is how I found myself rushing to take a seat at a Karakuri puppet show. Karakuri dolls are clockwork-driven creations originally from the Edo period; their most famous incarnation in Takayama is on elaborate parade floats that are brought out every year for the local festival. The floats are oddly tall and skinny, and I walked past a couple of three-storey garages in town with very tall doors where parade floats are stored. The karakuri I saw were smaller than parade float ones, ranging in size from about 18” to 36” high. They were quite impressive, too. Controlled by a series of rods and mechanisms, there was a karakuri that could climb steps with nothing connected to the bottom of his feet, one that swung through a series of trapezes, and even one that could write calligraphy on a piece of paper. I managed to get a video of part of the show, which was completely fascinating and charming:

Karakuri in action

I mentioned that Takayama has an excellent stock of historical homes, and I toured through two of them that have been preserved in the northern end of the city. Both had been home to merchant families and were collections of tatami mat rooms, large and small, that could be reconfigured with sliding screens. The screens might be opened to allow a view of the garden, or closed for privacy, or removed completely to join several small spaces into one for a large celebration. It’s a very different style of design than we’re used to in the west. Here’s an excellent introduction from a pamphlet I picked up at Yoshijima House in Takayama:

“The rooms with tatami, or straw mats, not only in Yoshijima house but in most traditional Japanese houses, possess no fixed function. The function of the room is determined by the objects which are placed in them. For example, by placing a portable dining table in a room, that room becomes a dining room. If fine zabuton, or floor cushions, are placed in the room, it is now a guest room; when bedding is placed in the room, the same room is transformed into a bedroom. Furthermore, the furnishings, hanging scrolls, etc., would be changed to fit the seasons or the ceremonies to be undertaken in a particular room.”

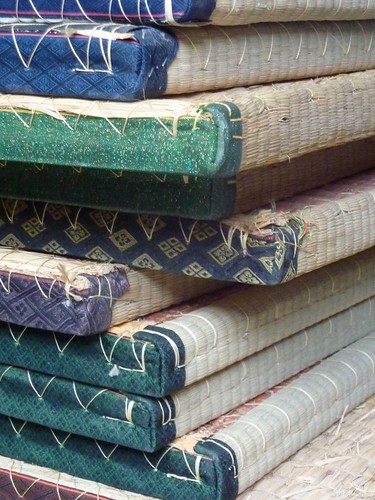

Again and again in Japan I’ve run into the “tatami mat” method of measuring floor space. The size of a single tatami mat differs slightly in different areas of Japan but is always around 3' x 6' and always a perfect 2:1 ratio. All of the indoor living space in the historical homes I’ve seen have floors covered with tatami mats, as have several hotel rooms I’ve stayed in. And whenever they describe a room in one of these historical structures they almost always start by telling you the number of tatami mats covering it. (“This 8-tatami mat room was used as a resting place for guests before blah blah blah…” or “This large 49-tatami mat room can be divided into three different spaces with the use of sliding screens.”). One of the most famous rooms at Ginkakuji is called the Four-and-a-Half Tatami Mat Room, capitalized here because that particular room came to be a model for similar rooms all over Japan. And I think this method of measuring space is still used today. When he saw the picture of my ryokan on Miyajima Paul was quick to point out that it was a 12 mat room, generous indeed since many modern apartments are only 8, or sometimes just 6 mats.

I also noticed that the importance of the room can sometimes be divined by the elaborateness of the binding along the sides of the tatami mats. The mats in servants’ quarters might have no binding at all, whereas everyday rooms could be bound in plain black or blue. And I saw rooms for important guests or for the master or mistress of the house where the tatami mats had been bound in patterned fabric.

A stack of tatami mats in a shop in Takayama

A stack of tatami mats in a shop in Takayama

And it’s not just the historical homes that display particularly Japanese characteristics. The modern places occupied by the normal people of Takayama were wonderful too, in a very Japanese way. For instance, windows facing onto the street are almost always frosted or covered in rice paper. In addition there’s usually a slatted wooden screen of some kind in front of that and sometimes a bamboo blind hanging in front of that. Very private, and so very Japanese. And the gardens in front of the houses are fabulous too – compact, spare and thoughtful.

I loved wandering through those traditional Japanese homes with the tatami mats, the sliding rice paper screens and the woodwork burnished to a smooth, deep brown colour. Again and again I’d turn a corner and be faced with some perfectly designed space with a single scroll of calligraphy hanging in an alcove and a view over a fantastic garden; it was all really peaceful and calming, and I liked it very much. As I get closer to having my own space again I wonder how much my experience in Japan will affect how I chose to design where I end up living. I don’t think I could manage the completely empty look – I like a good couch and a proper bed too much for that. But Paul’s words echoed in my head as I stood in those rooms and my mind whirred thinking about how I might fit my own life onto 8 tatami mats. I’m definitely going to miss life on the road, but at the same time I can’t wait to get back and see how it all unfolds.

4 Comments:

Well said.

I'm in love with the four stick fire in the sandal workshop. I think I could have sat quietly in that room for a long time.

Ian

this is interesting. Thanks for sharing fabulous information.

This is a really detailed and helpful tutorial! I like how you broke down each step of wrapping, trimming, and edging the mats—it makes the whole process feel much less intimidating. The use of double-sided tape and the template trick for getting clean fabric edges is especially clever. It also reminds me how traditional tatami mats pair so well with a japanese futon mattress, since both emphasize simplicity, portability, and a natural aesthetic. Seeing your DIY approach makes me appreciate the craftsmanship even more, and it gives me ideas for setting up a minimalist sleeping space at home. Thanks for sharing the process!

Post a Comment